Climate change linked to longer allergy seasons across the U.S.

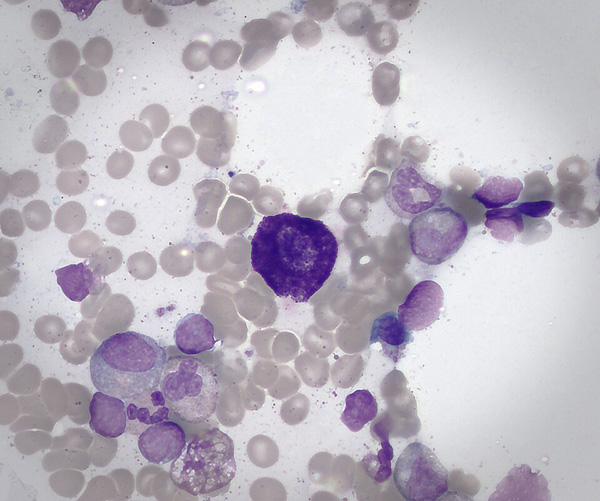

[A photo of a mast cell. Photo Credit to Wikimedia Commons]

In 2025, the nonprofit group Climate Central reported that nearly 90% of U.S. cities have experienced freeze-free growing seasons that have extended since 1970.

This shift means more days of sunlight and warmth, allowing plants to grow for longer periods and release greater amounts of pollen.

For millions of people, that translates into prolonged and more intense seasonal allergies.

But why do harmless particles such as pollen or flower proteins cause symptoms like coughing, sneezing, or watery eyes?

The answer lies in allergies, an overreaction of the immune system that treats harmless materials as if they were parasitic invaders.

Although the discovery of allergies dates back to the mid-1900s, one strong hypothesis suggests their origins may be connected to the earliest days of human civilization.

Early societies struggled to keep drinking water free from waste, which allowed parasitic worms to thrive.

These worms would be consumed through contaminated water, enter the body, and roam freely for up to decades.

Once ingested and later excreted in waste, these parasitic worms lay eggs, repeating the cycle endlessly.

To fight such organisms, the human immune system developed powerful defenses.

Among these are mast cells, which function like microscopic grenades, packed with chemicals capable of killing invaders but also damaging nearby health cells.

Here’s how the process works: dendritic cells detect what appears to be an intruder and activate B cells, the body’s antibody factories.

These antibodies attach themselves to mast cells, priming them to release their chemical arsenal at the next encounter.

When a parasite enters the body, mast cells erupt, helping to destroy it.

Over centuries, this system proved effective against worms and other invaders.

However, with advances in sanitation, clean water, and hygiene, many parasites disappeared.

The immune system, though, retained its arsenal.

Today, mast cells and other defenses sometimes misfire, responding to harmless materials like nut proteins or pollen as though they were deadly threats.

The result is the chain of symptoms now recognized as allergies.

Scientists still debate why some people produce more mast cells or why allergies can appear and vanish throughout life.

What is clear is that allergy rates are rising.

Between 2000 and 2018, the number of children with allergies doubled.

There are many speculations about the cause, but the most widely noted is climate change.

Longer, warmer seasons lead to longer and more severe pollen seasons, which air pollution further irritates respiratory systems.

Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane not only fuel climate change but also stimulate plants to produce more pollen.

Areas that once had cold climates now host pollen-producing plants, spreading allergies to new regions.

Today, more than a quarter of U.S. citizens report experiencing seasonal allergies.

Although treatments such as antihistamines and epinephrine injectors can ease symptoms, the root challenge is expected to expand as the climate warms.

- Aiden Park / Grade 10 Session 9

- The Stony Brook School

![THE HERALD STUDENT REPORTERS [US]](/assets/images/logo_student_us.png)

![THE HERALD STUDENT REPORTERS [Canada]](/assets/images/logo_student_ca.png)